The old red family album is falling to pieces – pages empty, gaps and glue marks on the thick black paper. Prints are dispersed around the house, the museum of our lives randomly curated and re-curated on the mantelpiece like the shuffling and muddling of memories. Objects, photographs, articles and other mementos appear, sit together for a while, and then disappear as we shake the kaleidoscope and the story’s emphasis shifts. The clock stopped some time ago at five past two, but mantelpiece-time does not stand still. It’s all snapshots and vignettes and fragments from up and down the decades.

Something about middle age, something about the shock of sudden losses and the slow creep of anticipatory grief, something about the thread of dementia that winds its way down the generations – something about all this compels me to set a narrative down, to fix the past, and the present too, before it all slips from my grasp forever, before I too forget.

But each time I shake the kaleidoscope, a different picture forms.

This is one of those pictures.

My mother’s photographic life began in the mid-1960s, when, as a teenager, she started work as a museum photographer at the Ashmolean in Oxford. The experience has remained very much part of her identity; she still tells stories of those days.

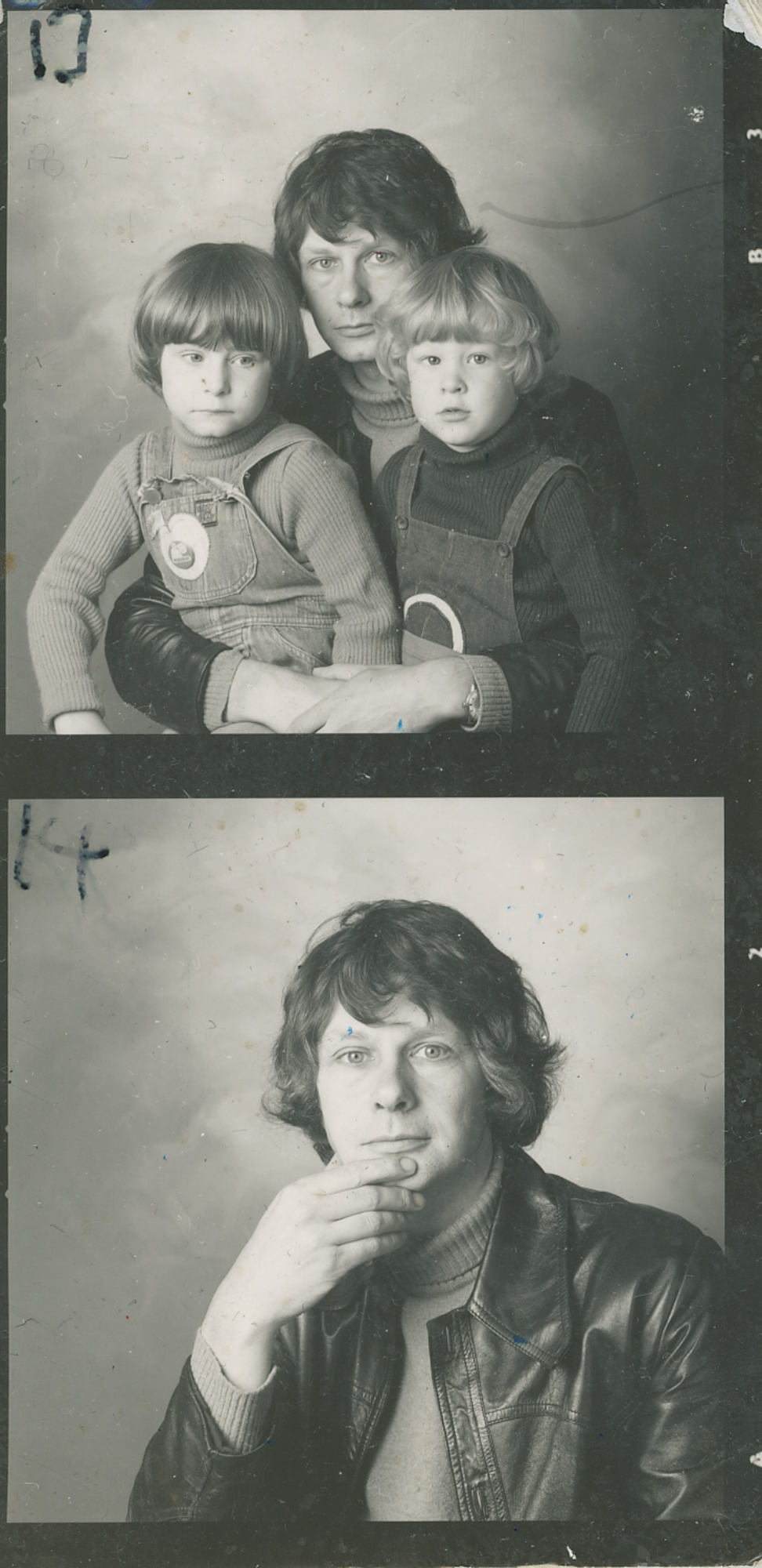

In 1968 she married David Carpenter. David (himself from a family of photographers) was a photography student at the London College of Printing: he stayed onto teach there for the whole of his working life. Through Oxford University they rented a cold, damp, thatched cottage a couple of miles off the road at Nuneham Courtenay. They had a studio on Oxford High Street, but the tumbledown outbuildings at home made for great photography, and the two were granted permission to carry out freelance photographic work from the house. An afternoon in that archive is like a shake of that kaleidoscope.

Caroline left the Ashmolean when I was born, and later changed career completely. But photography remained central to her life for a long time. My earliest memories are of the darkroom at home, all red lights, chemical smells, and magic. While my father taught me semiotics, my mother taught me how to light a face. It seemed to me that photography was not only embedded in the family identity, but also forever associated with that cold, damp, wonderful house on the edge of the woods.

Photography has threaded its way down the family line, and so too has Alzheimer’s disease. My maternal grandmother Ruby was diagnosed in the mid-80s. She came to live with us, and there were good, if sometimes difficult and chaotic times. Joy in her last years came from singing old songs to my new brother, and from walking.

One afternoon in 1990, apparently by accident, Ruby wandered on to the railway line. She was hit by an oncoming coal train and died in the John Radcliffe Hospital later that evening.

Fast-forward three decades, and both photography and dementia have continued their paths down the generations. Caroline’s older sister Pat was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease about six years ago. Caroline, too young by far, got her own diagnosis a little while later: Posterior Cortical Atrophy variant Alzheimer’s. Before it comes for the memory, it attacks the visual processing centres in the brain; the world becomes contorted, distorted, unrecognisable. My mother can no longer use a camera.

March 2020, and in the space of two short weeks, the following happens. My father, 14 days after routine surgery, drops dead in the street of a pulmonary embolism. A week later, my mother’s beloved, creaky old cat joins him. And not a week after that, on the first day of the Covid lockdown, my aunt’s dog goes too.

Pat moves in with Caroline, each sister battling her own losses and form of dementia. The law permits us to visit and take care of them together. They escape Covid – for now – but the isolation is pernicious.

Here they remain. It is not easy, but they are brilliant, resilient. Old songs bring joy, and so does the garden. Dave’s ashes are there, under the standard box tree that my mother tends, scattered together with the cat’s. Next to the shed, the dog’s grave that my brother dug by torchlight. In the house, the old objects, prints, snaps and articles that convene and reconvene on the mantelpiece. Shakes of the kaleidoscope.

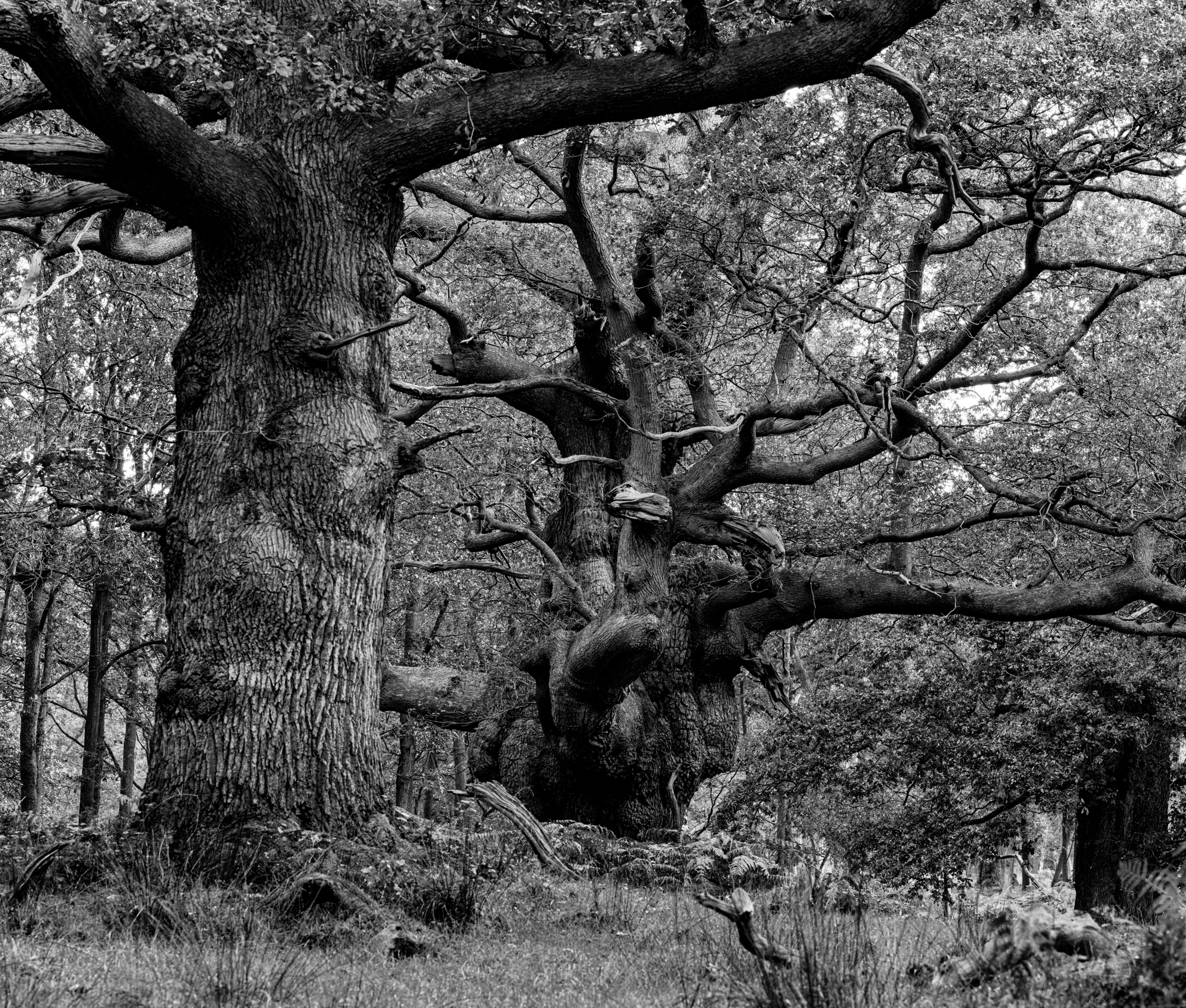

And here I am, still reeling from the shock of the loss and the relentless anticipatory grief. I am glad of the consolations of photography as I muddle my way through and reflect on what it all means for me. The very act of photography is an act of nostalgia; it has threaded its way down the generations of my family and is a homecoming of sorts. As for the other thread – of course, I wonder whether that is coming for me too. In response, I think, I’m drawn to the woods, to the uncanny, tangled fractals of the trees, where I can at once play with my fears and simultaneously keep them at bay.

Anticipating the losses and the forgetting to come, I photograph life in that house, in that home that we seek to keep happy for as long as we humanly can. Aunty P is gone now too, and the contorting rooms grow ever more uncanny; there are strangers in the mirrors and crowds behind the walls. Lightbulbs flicker as we sing the favourite old songs. The standard box has got a case of blight.

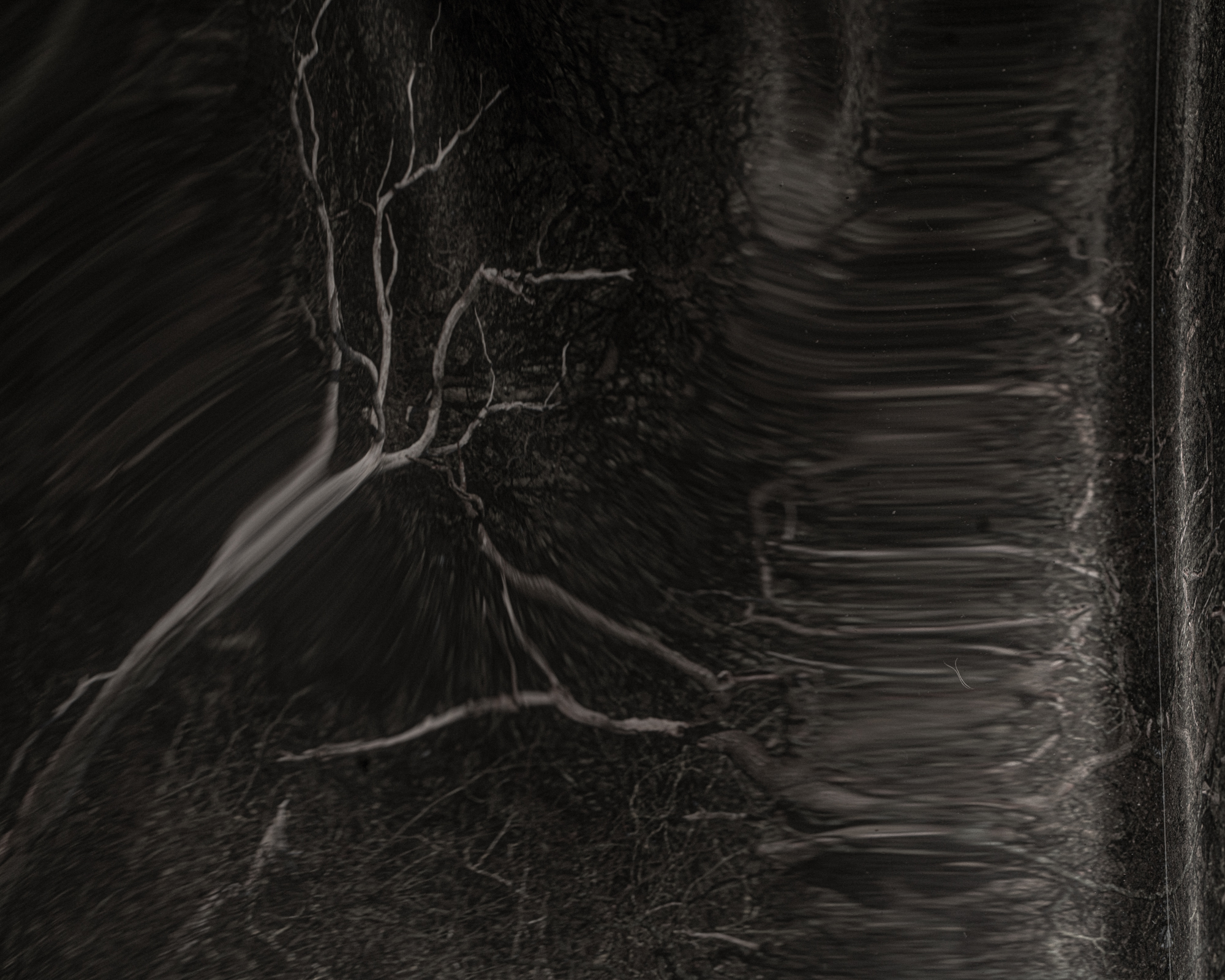

Above: To make these images, I print woodland images on textured paper, reflect them in distorting mirrored material

and photograph the reflections with a macro lens. With this process, I’m trying both to understand and to express the

uncanny visual disturbances that my mother describes.

With my mother’s blessing and companionship, I set out to tell a version of her story, and with it, a part of my own.

I wasn’t sure I had the strength to go through the jumbled boxes that make up the family archive – the grief was still too raw, the nostalgia still too bitter. But there was comfort in the process too. I wanted above all for the story to avoid pity. I didn’t want the trajectory to be defined by loss alone. So I scanned, I re-photographed, and I printed, and I stuck the lot up on a big blank wall along with my pictures from these last dark years. And when I looked at the prints, what I saw on the wall was not so much loss, but love and connection.

I end at the very beginning, at the place the story began, with a party at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. A rather grand old place to launch my quiet book, but the only choice I could have made. Peeling back time and layers of memory, somehow Caroline knew where she was, and why. She sparkled. The party felt like a celebration of my mother’s life, and an expression of all the love and connection I had seen when I stuck those photographs up on my blank wall.

There are dark days ahead, I know. But with my camera for a kaleidoscope, I can keep turning the view to look at all the joy that, despite everything, still remains

This piece is an edited version of the text in Kate Carpenter’s photobook, Kaleidoscope.

About Kate Carpenter

Kate’s photographer parents brought her up with a love of photography; her childhood memories of darkrooms, red lights, and chemical smells have not faded. She studied English and Modern Languages and has taught in schools and colleges in the UK, Germany and Belgium. Kate later undertook an MA in Education and a Law degree, after which she spent several years as an advice centre volunteer, and running private and pro bono photography workshops.

Wishing to bring all her interests together under a photographic umbrella, Kate recently completed a Master of Arts in Photography at Falmouth University. Her work touches on themes of family history, memory and forgetting; it combines archival, documentary and landscape imagery. Kate is also interested in the power of photography as a therapeutic tool.

Kate’s photographic work has been exhibited in the UK and the USA and has featured in various print and online publications.

Kate’s book, Kaleidoscope, is available from:

www.instagram.com/kvcarpenter/