A relative newcomer to “serious photography”, I have been struck by two things. Firstly, most of the creative photography workshops that I have been to have overwhelmingly been led and attended by women. Secondly, both historically and currently, many spaces and places where photography and photographic equipment are discussed, displayed, demonstrated and sold are dominated by men. Why is this? This question was reinforced as I became interested in Abstract Expressionism and its links with photography.

During two recent talks on Expressionism, both speakers drew mainly on the work of male photographers, referencing only a handful of women. Where was the work of female image creators over the past century? Was their work considered too trivial or unimportant? Were they simply underrepresented? Or was their work deliberately excluded?

All this fuelled my interest in Abstract Expressionist photography. My initial research revealed that there had been a significant number of female pioneers, lesser known but often very influential. In wanting to highlight their contribution, I started with the fascinating life and work of Florence Henri, intrigued by her innovative use of light and reflections.

A visionary

Born in the USA in 1893, Henri spent her childhood in Europe. An orphan by age 14, she had inherited a small income which gave her the means to pursue an artistic career and quite possibly fostered her independent and individual approach. In the 1920s she studied painting at the Bauhaus in Germany, mixing with the emerging avant garde community there before settling in Paris and studying under the Cubists Lhote and Léger whom Henri credited with having the most influence on her work. Her paintings and collages became more abstract and incorporated Constructivist geometric forms. I was amazed to discover that in 1925 this “unknown” artist had had her paintings exhibited alongside work by Klee, Mondrian and Picasso.

Clearly Henri was very talented and became recognised within the avant garde circle as a visionary artist whose work was making an impact on the evolution of modern art. It was only in 1927 that she turned her attention to photography, enrolling again at the Bauhaus. One of the key influencers there was the Hungarian Constructivist artist and New Vision photographer László Moholy-Nagy, and his wife Lucia. Henri embraced the emerging new technologies in photography, using multiple exposures

and photomontage. Her self-portraits challenged conventional notions of identity and representation, and she was fascinated with the visual possibilities of everyday objects reflected in mirrors.

After only two years studying photography, Henri opened her own studio in Paris, focusing on portraiture and later on advertising. In the 1920s and ’30s, she was clearly renowned for her photography and also influenced other female photographers such as Lisette Model and Ilse Bing. And yet Carole Naggar, writing about Henri in 2015, called her one of photography’s unsung influencers. Why has her contribution faded into obscurity, when the names and work of her male contemporaries are still well-remembered? It is difficult to understand.

Subverting convention

In an attempt both to explore the nature of her influence and unpick what makes Henri’s work inspiring to me, I set myself the task of analysing what is distinctive about her photography and to try some of her approaches. When one examines her work closely, it shows that she deliberately looked to subvert conventional photography. She played around with notions of identity and captured vulnerabilities with her portraiture. The most famous example is this self-portrait, with two silver balls.

I find particularly interesting and stimulating her exploration of perspective and lines through the use of mirrors in portraits and still life compositions to isolate, frame, double or triple the subject, leading the viewer to wonder what is reality and what is reflection. Whenever Henri has direct control of the composition, she incorporates circles and orbs, lines and rectangles, sharp angles, reflections and shadows. When she is out of the studio, she continues to seek out these elements. In her street photography, she often uses shop windows as the mirrors, dividing what is inside and outside, with creative reflections. Her industrial architecture images also centre on grids, lines and circles. Thus there are continuous threads of interest to follow through her body of work, which I focused on as a stimulus for my own photographic experimentation.

I decided to experiment with some of Henri’s approaches. I started with portraiture, making some key decisions before I took any images. Henri had used a Leica camera with a 50mm lens so I opted for my Canon EOS R in order to use the same lens. This immediately introduced a challenge for me as I am so used to being able to compose images through zooming in and out. With the 50mm lens I had to move my feet instead! I chose monochrome and a 4x3 crop, to fit with Henri’s work. Lacking my own studio, I chose to take the photos in the room in the house that has plenty of natural light and mirrors – the bathroom! And I found my model there – great timing!

Next I turned to still life. I identified the elements that made Henri’s work distinctive and set about recreating some images. I confined myself to just using objects that I already had in my home, in the way that I envisaged she did with her experiments in her home and studio.

My first attempts with a mix of fruit and mirrors showed me how difficult it was to set up the composition precisely to get the range of reflections I was aiming for. But I continued to experiment, introducing more elements and reflective surfaces:

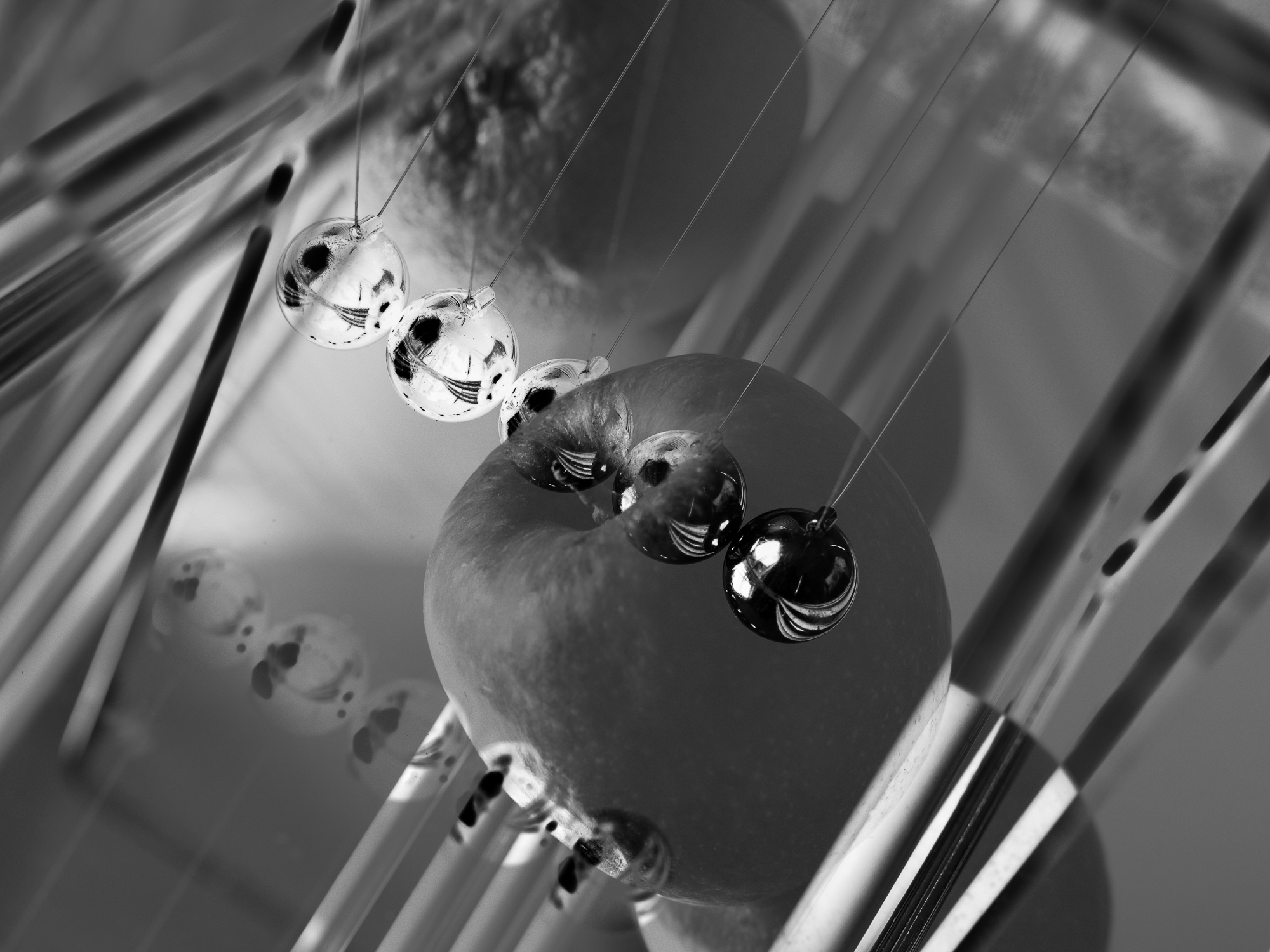

I realised, though, that I also needed to think about introducing spheres and lines, and all I could find was a Newton’s Cradle. It had to do; at least the spheres were reflective:

Henri was also known for experimenting with double exposure and photomontage. I wonder what she would have made of Photoshop! Here I use Photoshop to combine images, applying different blend modes to preserve the shapes of the fruit, while retaining an abstract feel overall:

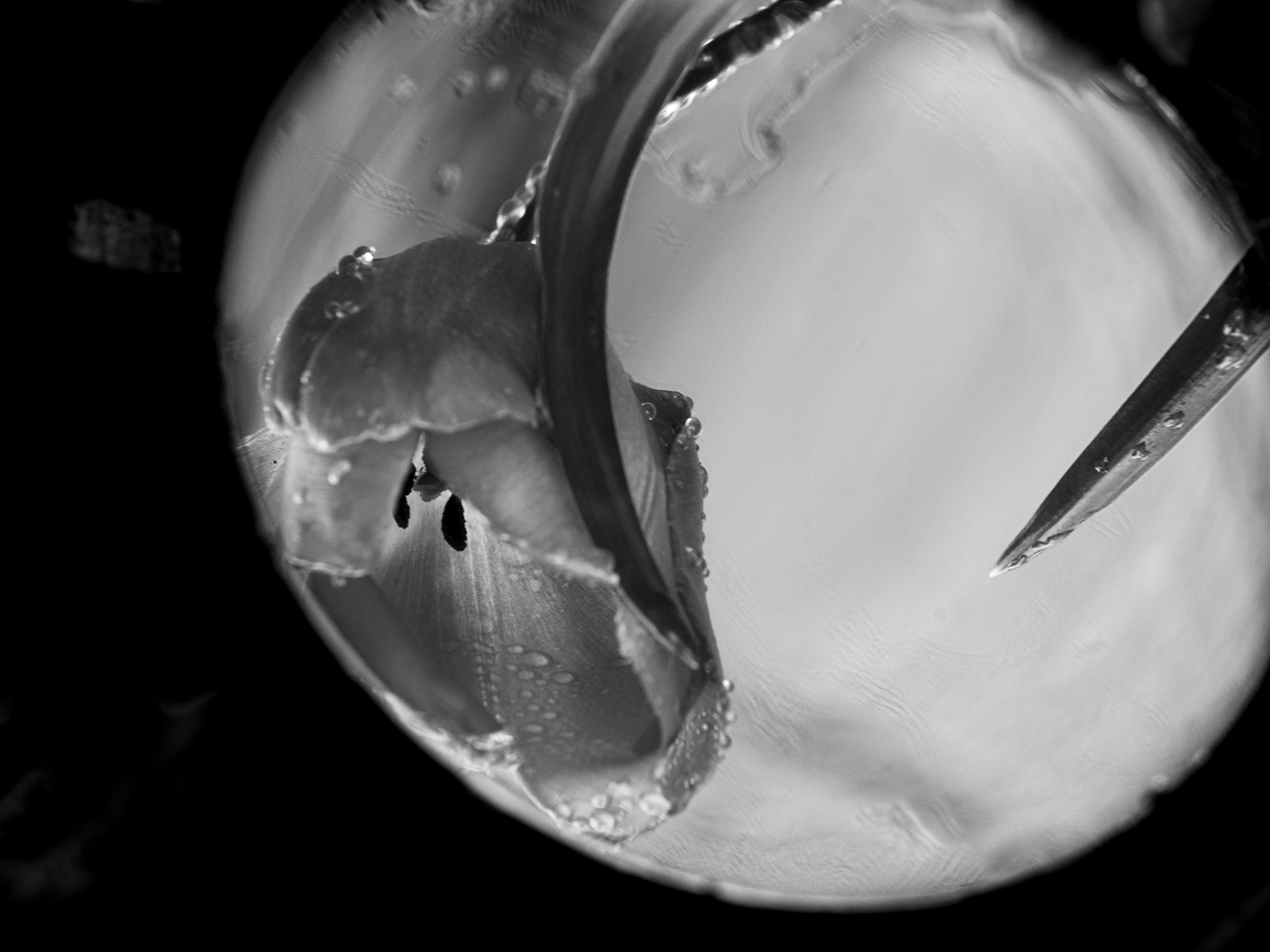

And in this image the raindrops on the petals are topped with silver spheres and lines, representing many of Henri’s motifs:

This image takes the abstraction much further, with several layers and a darker blend mode, to emphasise the lines and shapes of the dying petals of the tulips:

Undertaking this research is challenging me to go out of my comfort zone, into portraits and still life, homing in on composition. I am learning that using monochrome focuses my attention on contrasts such as light and dark in an image because there is no colour to distract the eye. Working on this project based around Florence Henri’s work has hugely enhanced my respect for her creativity, her innovative approaches and her imagination. She continues to shape what I turn my attention to, and to enable me, however imperfectly, to challenge and question perceptions of reality, just as she did almost 100 years ago.

About Valerie Huggins

Valerie Huggins is an amateur photographer, based in the South West of England. Since stepping back from a high pressure career in education, Valerie has enjoyed developing her photography, taking an increasingly experimental approach and seeking out new challenges. She uses creative techniques such as ICM and multiple exposure to create alternative realities and to generate visual narratives.

Mindful of the lack of attention given to women photographers historically, Valerie is currently researching the female gaze through abstract photography from the 1920s onwards for an RPS Research Licentiate.